Two of the Big Boys (the two biggest?) of bicycle component manufacturers, Shimano and SRAM, have both created quite a lot buzz with their patent applications for drivetrain components which would, in different ways, eliminate the front derailleur.

Two of the Big Boys (the two biggest?) of bicycle component manufacturers, Shimano and SRAM, have both created quite a lot buzz with their patent applications for drivetrain components which would, in different ways, eliminate the front derailleur.

What I think this shows if that even the Big Boys realize there are inherent problems with the front derailleur on drive trains and that they have invested significantly in R & D and patent costs and fees to come up with creative, albeit super-complicated ways around what has been a mainstay of bicycle transmissions.

The fact that these major players in the bike component marketplace are looking seriously at alternatives to the front derailleur has driven interest in VECTr.

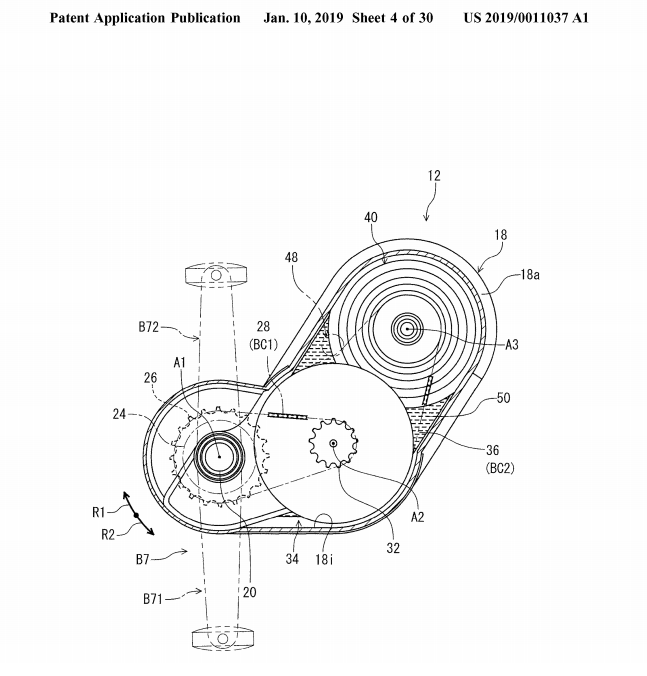

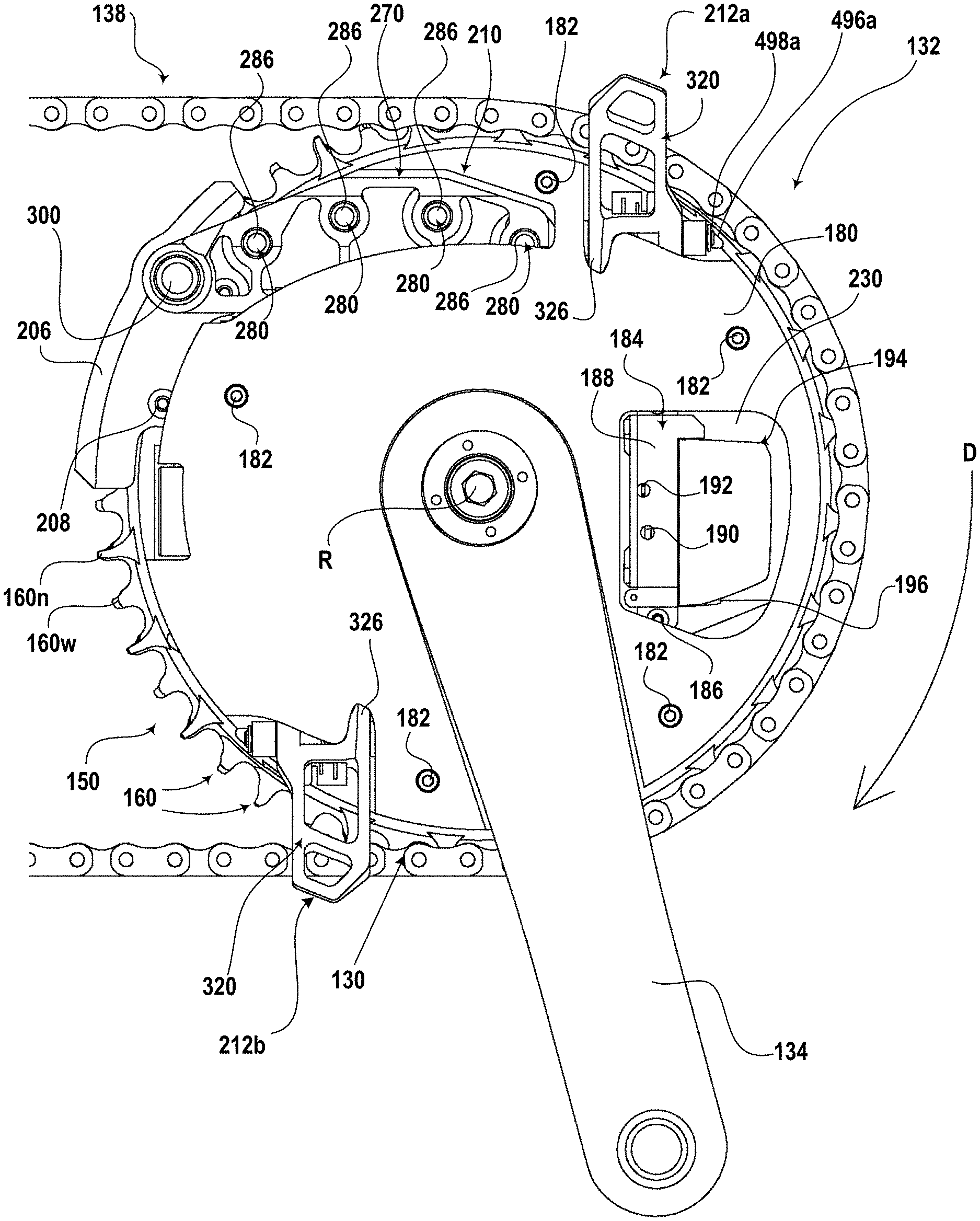

VECTr similarly eliminates the front derailleur and instead varies the size of the front driving gear by adjusting crank mounted gear segments. This keeps the chain in a consistent chainline. Shimano’s gearbox would do this, but only by requiring a heavy, complicated mechanism built into the bicycle’s frame. VECTr achieves gear changes while being mounted on existing bike cranks/bottom brackets, components compatible with standard frames. SRAM’s device would seemingly do this too, but it would also itself be a true derailleur and push the chain between only two discrete chainrings. Moreover, it would do so by incorporating tiny servo motors, batteries, a radio receiver, a timing computer and who knows what all else.

VECTr similarly eliminates the front derailleur and instead varies the size of the front driving gear by adjusting crank mounted gear segments. This keeps the chain in a consistent chainline. Shimano’s gearbox would do this, but only by requiring a heavy, complicated mechanism built into the bicycle’s frame. VECTr achieves gear changes while being mounted on existing bike cranks/bottom brackets, components compatible with standard frames. SRAM’s device would seemingly do this too, but it would also itself be a true derailleur and push the chain between only two discrete chainrings. Moreover, it would do so by incorporating tiny servo motors, batteries, a radio receiver, a timing computer and who knows what all else.

VECTr’s very great advantage over these proposed alternatives from SRAM and Shimano is that it achieves the same or better result than the devices described in the patent applications with a very much simpler design, and no doubt, at a very much reduced cost. Plus, VECTr is already patented!

Three years to the day after I filed the non-provisional patent application with the US Patent and Trademark Office, the examiner has allowed a patent for my Variably Expanding Chain Transmission to issue! Once the Notice of Allowance is mailed, and after I pay the requisite fee and submit any required changes or corrections to the application, the patent should issue in a few weeks! At that time, VECTr will no longer be “patent pending,” but an actual patented invention!

Three years to the day after I filed the non-provisional patent application with the US Patent and Trademark Office, the examiner has allowed a patent for my Variably Expanding Chain Transmission to issue! Once the Notice of Allowance is mailed, and after I pay the requisite fee and submit any required changes or corrections to the application, the patent should issue in a few weeks! At that time, VECTr will no longer be “patent pending,” but an actual patented invention!

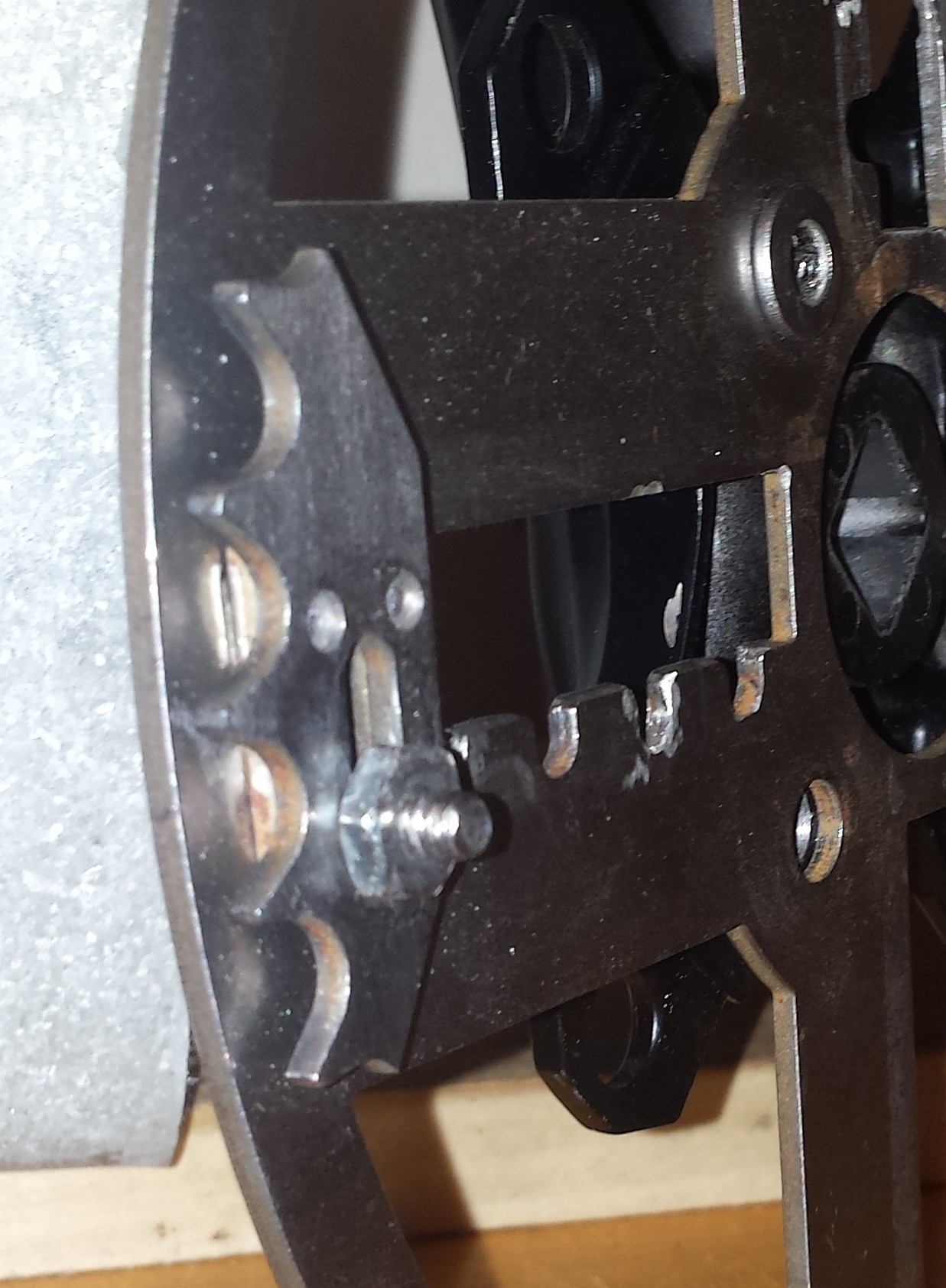

Finally, I found that by modifying the inside control plate from the old design, it would contact the locking pin on the gear segment at an appropriate angle to unlock it and slide it to the desired radial position. (It took much trial and error to find the appropriate angle — a better understanding of geometry and the physics of friction might have led to a good design, a priori, but what can you do . . . .)

Finally, I found that by modifying the inside control plate from the old design, it would contact the locking pin on the gear segment at an appropriate angle to unlock it and slide it to the desired radial position. (It took much trial and error to find the appropriate angle — a better understanding of geometry and the physics of friction might have led to a good design, a priori, but what can you do . . . .)

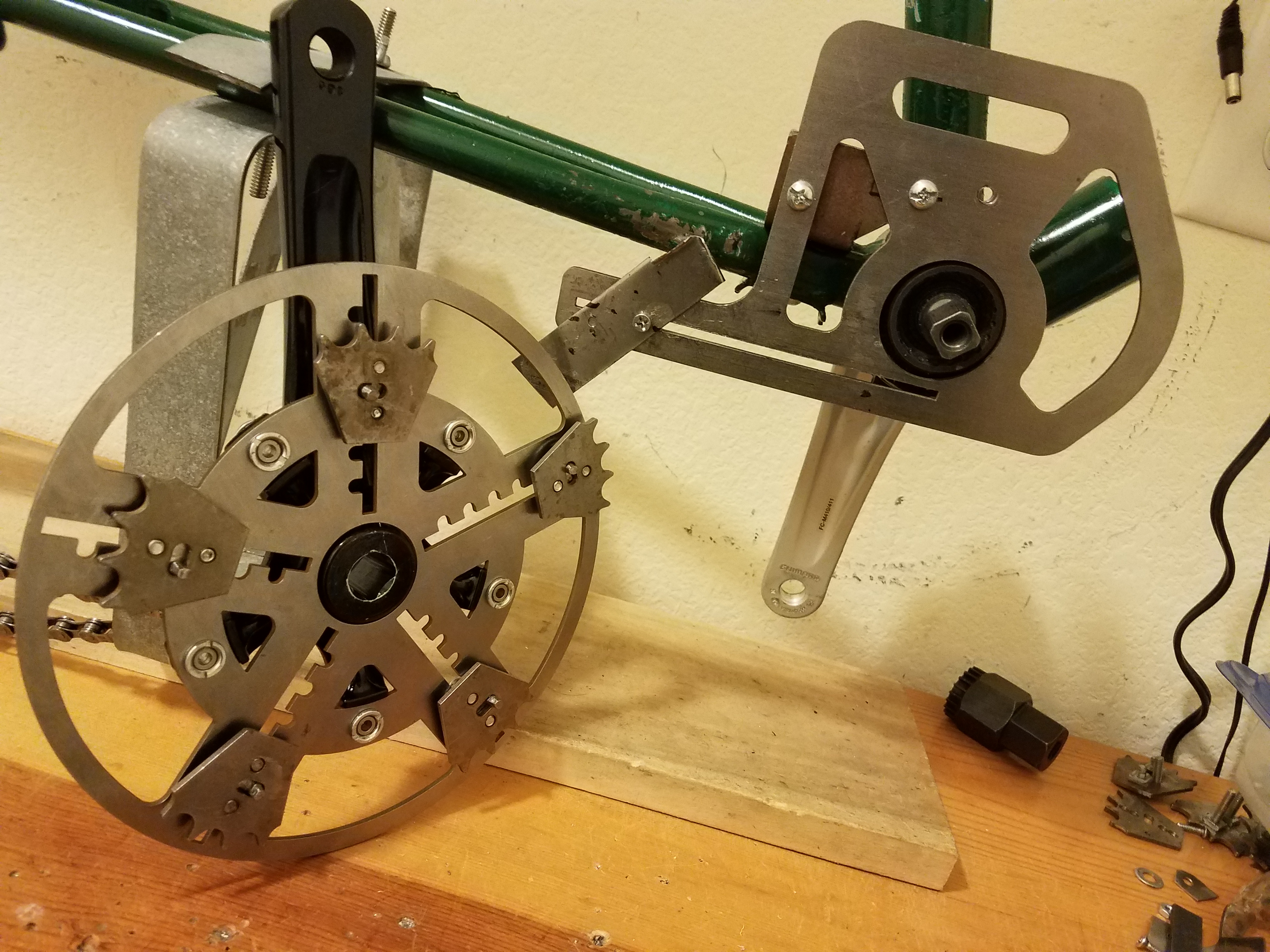

There were concerns specific to the VECTr design which I have spent my time trying to address. The first had to do with the smoothness of the operation. It has always been an aim of the design process to make a device which is compatible with current bicycle standards, and so I made a four gear segment mechanism which could be fitted to the 64 BCD fittings of a MTB crank arm.

There were concerns specific to the VECTr design which I have spent my time trying to address. The first had to do with the smoothness of the operation. It has always been an aim of the design process to make a device which is compatible with current bicycle standards, and so I made a four gear segment mechanism which could be fitted to the 64 BCD fittings of a MTB crank arm. Also, the design of the locking/adjustment mechanism of the gear segment consisted of three pieces for the sliding motion, plus a pin/bolt and spring for the locking motion, in addition to the actual chain-engaging gear segment. These were all held together with simple blind rivets, which I knew were none too strong, and probably would not hold up to the stresses of actual road use. In working up some cost estimates for the manufacture of VECTr in that iteration of the design, it became clear that it would be difficult to entice a manufacturer to license the design, or for me to make them out of my garage. I thought, too, that simplifying the design of the gear segment mechanism would decrease the weight and offset the additional mass of added gear segments.

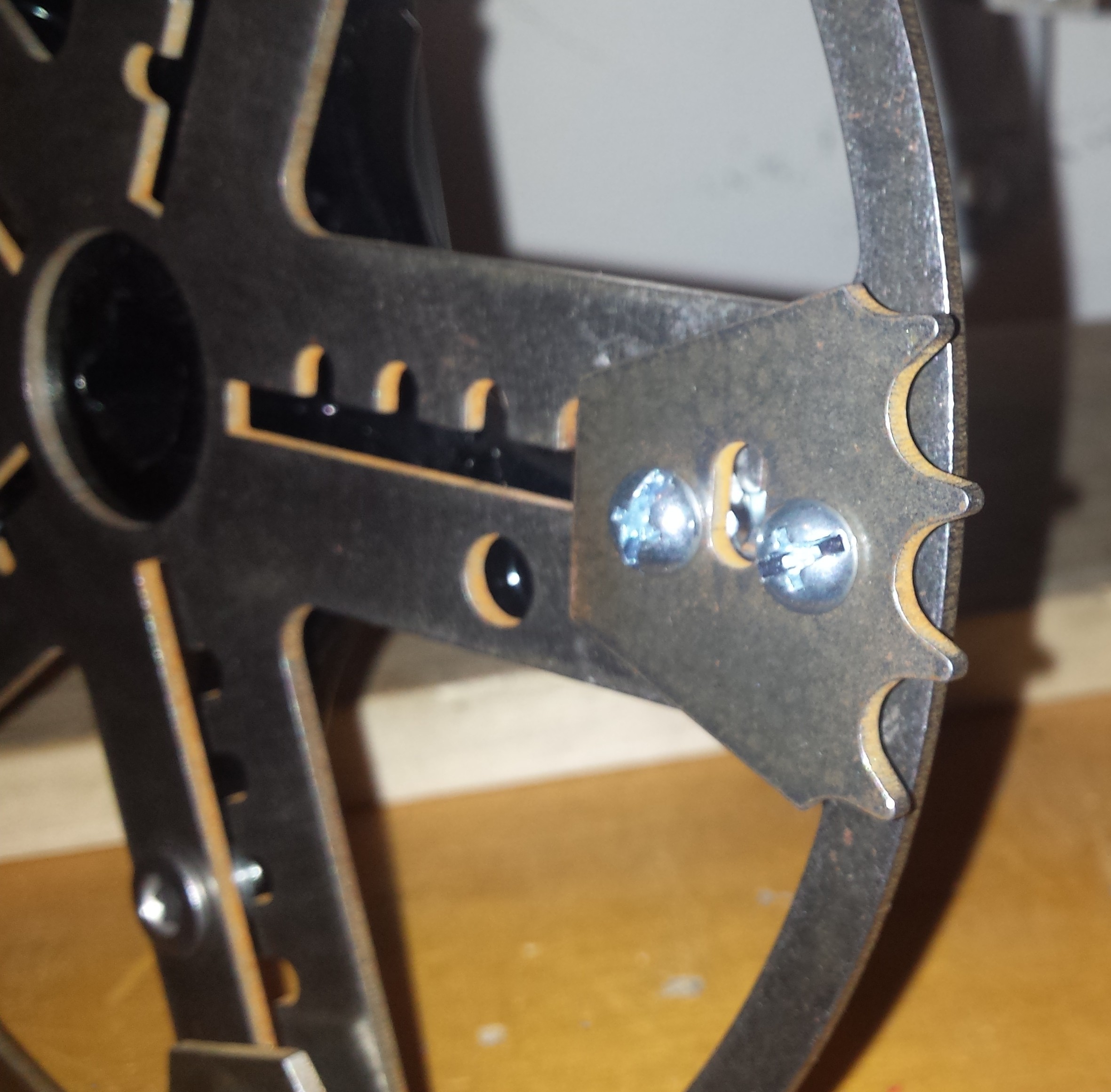

Also, the design of the locking/adjustment mechanism of the gear segment consisted of three pieces for the sliding motion, plus a pin/bolt and spring for the locking motion, in addition to the actual chain-engaging gear segment. These were all held together with simple blind rivets, which I knew were none too strong, and probably would not hold up to the stresses of actual road use. In working up some cost estimates for the manufacture of VECTr in that iteration of the design, it became clear that it would be difficult to entice a manufacturer to license the design, or for me to make them out of my garage. I thought, too, that simplifying the design of the gear segment mechanism would decrease the weight and offset the additional mass of added gear segments. The result of rethinking these issues led me to design VECTr with five expansion arms (fitted for 110 BCD cranks) and five gear segments which would slide within narrower channels, still having notches on one edge into which a locking pin would fit. In a

The result of rethinking these issues led me to design VECTr with five expansion arms (fitted for 110 BCD cranks) and five gear segments which would slide within narrower channels, still having notches on one edge into which a locking pin would fit. In a  In this new design, I replaced the three-piece sliding parts with simple bolts (which also took the place of the rivets) and the locking bolt sliding with the rest; it would be biased into locking position by an external elastic band or other small spring.

In this new design, I replaced the three-piece sliding parts with simple bolts (which also took the place of the rivets) and the locking bolt sliding with the rest; it would be biased into locking position by an external elastic band or other small spring.